The Boids

"The Boids" examines the way computer graphics has been used to justify political ideologies in the past, and prompts us to examine how that is happening today. It questions our commitment to the libertarian, techno-utopian ideology that has permeated the internet since the 90s.

As artists and coders, what role does our work play in shaping the future?

Techno-utopianism, Silicon Valley's guiding ideology, combines the attitudes of the 60s counterculture with libertarian philosophy. As such it is strongly opposed to centralised control of all kinds. Political theorists often advance the argument that it is necessary for us to accept the social contract, i.e. that it is necessary to give up some freedoms in return for the maintainence of social order by a sovereign power.

Techno-utopians disagree. They believe that order can arise without centralised control, and that self-organising systems, like the Boids algorithm, demonstrate precisely how this can happen. In the 90s they believed that decentralised networks would free us from overbearing bureaucracies and authoritarian government control. Today, they believe that decentralised systems will free us from the control of the very thing their ideology led to: large tech platforms.

The liberation they promised us has not only failed to materialize but has been actively hampered by the technology they designed and the companies they built. Not only will this ideology fail to solve the problems of today, but it is morphing into something much more sinister.

We aren't flocks, and we don't have to be mobs.

Open edition released on highlight.xyz on 11th June 2024.

Background

In Silicon Valley in 1986 a young computer scientist by the name of Craig Reynolds made a remarkable discovery. He realised you could describe the flocking behaviour of birds with a few common sense rules. More surprisingly, he had no background in biology, and his discovery had required no empirical research. He formulated some obvious rules for each bird to follow - align with the closest birds, don't fly too close to them, and don't stray too far from the flock - and with a little tweaking on the computer the desired behaviour emerged.

Here's his original demonstration video:

Boids, Craig Reynolds, 1986

Discoveries such as this electrified the Valley. His algorithms were soon powering CGI in Hollywood blockbusters like Batman Returns. But for some this algorithm had much more significant consequences.

Techno-utopianism, Silicon Valley's guiding ideology, combines the attitudes of the 60s counterculture with libertarian philosophy. As such it is strongly opposed to government control of all kinds. In political theory it is frequently argued that, implicitly or explicitly, citizens accept a social contract with their government, which involves giving up some freedom in return for the maintainence of social order. But Techno-utopians believe that this is not necessary, because order can arise without centralised control. They think that self-organising systems, like the Boids algorithm, demonstrate precisely how this can happen.

In the early 90s, Wired magazine was the bible of Techno-utopianism. In 1992, its editor, Kevin Kelly, published a book called “Out of Control”. It attempted to demonstrate how the internet would revolutionise the world by harnessing the power of self-organising systems. Many of the systems were graphical systems that were first demonstrated at the SIGGRAPH conference, as the Boids was. In the book he also recounts an experiment of another CGI pioneer, Loren Carpenter (of Pixar), a couple of years later at the same conference:

In a darkened Las Vegas conference room, a cheering audience waves cardboard wands in the air. Each wand is red on one side, green on the other. Far in back of the huge auditorium, a camera scans the frantic attendees. The video camera links the color spots of the wands to a nest of computers set up by graphics wizard Loren Carpenter. Carpenter's custom software locates each red and each green wand in the auditorium. Tonight there are just shy of 5,000 wandwavers. The computer displays the precise location of each wand (and its color) onto an immense, detailed video map of the auditorium hung on the front stage, which all can see.

Loren Carpenter Interviewed by Adam Curtis in 2013

Carpenter booted up Pong onto the big screen. Kelly recalls screams of delight as the audience figured out how to return serve and began to play together, volleying the ball back and forth. Soon Carpenter gave them a more difficult challenge: flying a jet. Kelly continues:

The conferees did what birds do: they flocked. But they flocked self-consciously. They responded to an overview of themselves as they ... steered the jet. A bird on the fly, however, has no overarching concept of the shape of its flock. "Flockness" emerges from creatures completely oblivious of their collective shape, size, or alignment. A flocking bird is blind to the grace and cohesiveness of a flock in flight.

As Reynolds discovered, very complex forms of behaviour can emerge from only a few simple rules. Carpenter demonstrated that it is not even necessary to describe those rules explicitly. Given a goal and a sufficiently large network of agents, the network can figure out the rules itself. Both of these demonstrations show how order could arise in society without centralized control. There was nothing to fear from anarchy. Once we have the internet, we can simply do away with overbearing bureaucracies and stifling government control. What's more, they argued, to ensure positive outcomes the architects of these systems didn't even need to design the rules (or indeed the safeguards), as these were a form of centralized control. Just get people online, and they'll figure out how to make the world a better place by themselves, according to their own standards.

With hindsight, their naivety is stark. There are many words for flocks of humans, one of which is "the mob". Polemically, Kelly entitled the section I quoted above: “The Collective Intelligence of the Mob”. Yet another word for a human flock is a tribe. Rather than the anarchic libertarian freedom the techno-utopians dreamt of, the internet has brought a return of tribalism.

Later on in his book Kelly actually predicted that the internet was likely to divide any society that uses it into separate tribes with mutually exclusive world-views:

The fragmentation of business markets, of social mores, of spiritual beliefs, of ethnicity, and of truth itself into tinier and tinier shards is the hallmark of this era.

The tribalism that has emerged on social media has left societies divided, and diminished other forms of collective behaviour. Social networks suffer from vigilantism, witch-hunts and mob violence, which frequently spill over into the real world. Building and organising the kind of broad-based coalitions necessary to effect real change through protest (or even revolution) has become increasingly difficult in this environment.

After the 2008 global financial crisis many political commentators predicted that government attempts to impose austerity would meet resistance from powerful, social media-fuelled protests. But the movements that did emerge - The Arab Spring, Occupy, the various Colour Revolutions, UK Uncut, the Gilet Jaunes, the Five Star Movement among others - all failed to achieve lasting change. The liberation that the techno-utopians promised us has not only failed to emerge but is actively hampered by the technology they designed.

The techno-utopians knew the risks of the technology they were developing. In the same year Carpenter was staging his demonstration, a lawsuit sought to hold CompuServe responsible for the actions of their users. A subsequent lawsuit against Prodigy, another ISP, threatened to derail everything. Fortunately for the techno-utopians, several congressmen reacted to these judgements with alarm. The resulting act was dubbed "Twenty-Six Words Created the Internet". Instead of imposing liability on companies that tried to police their sites, these legislators wanted to leave Internet companies free to develop new and innovative services as the techno-utopians had dreamed of.

Commenting on this legislation in 2019, Wired acknowledged its terrible consequences following mass shootings in two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand:

In the immediate aftermath of the Christchurch attack, as Facebook and YouTube struggled to cope with the horrific footage flooding their platforms, it appeared that the internet was fundamentally broken. At YouTube, moderators scrambled to remove videos uploaded at a rate of one every second while Facebook blocked or removed 1.5 million videos in the 24 hours after the attack.

But the internet wasn’t broken. It was working exactly as designed.

By claiming that no controls are necessary on social media, the Techno-utopians have handed over control to the most powerful actors in society. Those who wish to spread disinformation, conspiracy theories, and hate-speech are able to do so, and there is little we can do to stop them. And again, because we are so divided, it is difficult to build a broad enough coalition to oppose them.

Today, the next iteration of Techno-utopianism is emerging. By financialising every online interaction with cryptocurrency, the pioneers of Web 3.0 think they will return the internet to the glory days of the 1990s. We desperately need to re-examine the commitment to the ideology that underpins all internet technologies. If we don't, we risk repeating the mistakes of the past.

We aren't flocks, and we don't have to be mobs.

Read More

- The Collective Intelligence of the Mob, from Out of Control, Kevin Kelly

- From counter-culture to cyber-culture, Fred Turner

- The California Ideology, Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron

- The strange story of Section 230, the obscure law that created our flawed, broken internet, Wired

- The 2010s: a decade of revolutionaries without a revolution, Will Davies

Technical Details

The following gives a basic technical description of the code for non-technical readers. If you would like a technical introduction to the algorithm and have some coding skills, the best place to start (as always) is The Coding Train.

The boids algorithm works by calculating the effect of three simple rules on each boid. Craig Reynolds' original paper delineates those rules:

| Separation: steer to avoid crowding local flockmates | |

| Alignment: steer towards the average heading of local flockmates | |

| Cohesion: steer to move toward the average position of local flockmates |

For each of these three properties, the algorithm works by calculating an average for either the velocity or direction of the boid (depending on which property we are calculating). This is then weighted according to a factor for the property and added to the boid's existing velocity or direction.

My initial experiments with the algorithm were not very successful. The first problem I encountered was that the boids would fly straight off the screen never to return. The most common solution to this problem was to add a fourth rule: when a boid gets near the screen boundary apply a turning force in the opposite direction. My initial implementation of this rather destroyed the flocking effect as the boids bounced around like rubber balls. After some tweaking I alighted on a solution: weaken the turning force, make the ultimate border off screen, and if the boids exceed the picture edge they are hidden until the turning force brings them back into the picture.

Early sketches showing dynamic movement

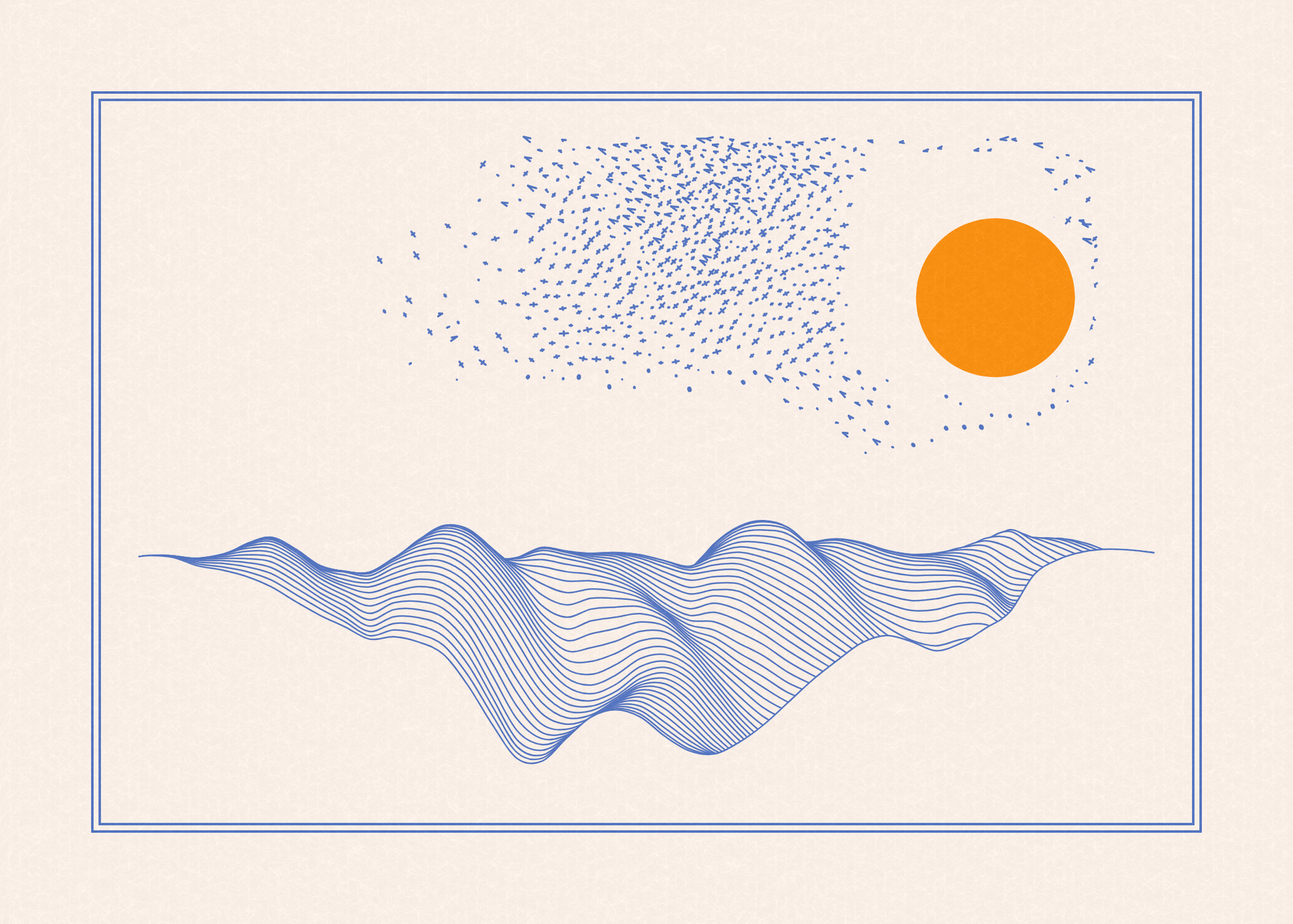

Another way to solve this problem would have been to have the boids track an object in the center of the screen. I was originally inspired to create this work by comments I saw on Instagram under a video clip of a murmuration. According to one commenter this was so extraordinary it must have been faked by AI. So I wanted this work to simulate a murmuration, not just generic flocking behaviour. According to several tutorials aimed at CGI developers, the only way to achieve a murmuration effect was to have several groups of boids track different objects. So much for self-organisation. In the code I refer to these objects as "shepherds", as they heard the flock around and control it. I experimented with different numbers of shepherds and different paths, and found that having two points following paths similar to those described by co-orbital planets produced the most realistic and pleasing effect.

Even though the boids are drawn extremely simply, simulating the movements of thousands of boids can be computationally expensive. The more boids you have, the more comparisons each boid has to make to calculate the effect of each rule. Even if we exclude neighbouring boids that are too far away, at minimum we still need to calculate the distance between every pair of boids. So for 100 boids, that would be 10,000 checks. For 10,000 boids it would be 100 million checks. In other words, this scales non-linearly (in fact O(n2) in the standard computer terminology). Therefore a basic grid system was implemented to reduce the number of calculations per boid. Only boids with neighbouring grid locations are checked and no distance calculation is required for this. This allowed creation of images with several thousand boids.

I realised I would need to draw upwards of 50,000 boids to properly simulate a murmuration. Even with a grid system in place, this is too much work for standard CPUs and would necessitate using the GPU. Whilst there are many projects out there that achieve this (with or without external libraries), drawing this many boids caused another problem: plotting the image on the Axidraw would still be extremely time consuming. I opted therefore to produce small prints with fewer than 2,000 boids so that a plot could finish in under an hour.

The code uses p5js-svg to export a plottable SVG of the image. It is designed to be plotted on A5. If you are using Inkscape you may find that the output from the SVG library has some image elements which need to be removed and the groups rearranged before you can plot this. If you are having any issues please contact me via email or Twitter.

If you would like to know more about the modelling of murmurations, which the Boids algorithm does not really handle well, please see the Quanta article in the references below.

Acknowledgements

- Coding Train 124, Daniel Shiffman

- GPU Boids implementation, Observable HQ

- Elliptic Curve ‘Murmurations’ Found With AI Take Flight, Quanta Magazine